Richard Trevithick

Richard Trevithick (April 13, 1771 – April 22, 1833), the 'Cornish Giant', was one of the most remarkable figures of the Industrial Revolution. He was a British inventor, versatile engineer, and builder of the first working railway steam locomotive. He clearly saw the advantages of using high pressure steam, and boldly put his ideas into practice, in the face of vigorous opposition from entrenched opponents.

General

1771 April 13th. Richard Trevithick born at Tregajorran the son of Richard Trevithick (Senior).

1771-90 See Richard Trevithick: Childhood.

1790 Trevithick's first job, at the age of 19, was at the East Stray Park Mine.

1792 He became associated with Edward Bull, supporting Bull's efforts to challenge the near-monopoly of Boulton and Watt.

1792 He tested and reported on the Jonathan Hornblower engine at Tincroft Mine.

1795 Re-erected an engine at Wheal Treasury

1795 Erected an engine at Ding Dong Mine, infringing the patents of Boulton and Watt

1796 Visited Soho Foundry with Bull and had an injunction served on him for infringing the Boulton and Watt patents.

1796 Modified the Ding Dong Mine engine to an atmospheric type

1796 Became acquainted with Davies Giddy later to become a close friend and adviser

1797 November 7th. Trevithick married Jane Harvey of Hayle at St. Erth. See Trevithick Marriage and Family. Jane was the daughter of John Harvey of Hayle Foundry.

1799 As Trevithick became more experienced, he made improvements to boiler design and construction, making them suitable for the safe production of 'strong steam'. This could be made to move a piston in a steam engine and then exhausted to atmosphere, instead of using a low pressure (close to one atmosphere) in a condensing engine. He was not alone in seeking to exploit the advantages of using high pressure steam. At about the same time Oliver Evans in the USA was developing high pressure steam engines and boilers, but it is highly improbable that Evans and Trevithick were aware of each other's work. Evans's first working high pressure engine was shown to the public in 1803[1]. In fact the genesis of the high pressure non-condensing steam engine goes back to Jacob Leupold in 1725, and in 1769 Cugnot produced the first self-propelled steam vehicle, using high pressure steam.

Not only would a high pressure steam engine eliminate the condenser but it would allow the use of a smaller cylinder, thus saving space and weight. In addition, the absence of a condenser, with its need for a good supply of cooling water, made it attractive in areas where water supply was problematic. Trevithick reasoned that his engine could now be more compact, lighter and small enough to carry its own weight even with a carriage attached. (Note this did not use the expansion of the steam, so-called "expansive working" came later).

Trevithick started building his first models of high pressure (meaning several atmospheres) steam engines, initially a stationary one and then one attached to a road carriage. Exhaust steam was vented via a vertical pipe or chimney straight into the atmosphere, thus avoiding a condenser and any possible infringements of Watt's patent. The linear motion was directly converted into circular motion via a crank instead of using an inefficient beam. Trevithick's widow frequently spoke of models of her husband's early engines, the first of which worked at her house in Camborne, about the year 1796 or 1797. It was made by William West, and was to have been shown in the lawsuits between Boulton and Watt and the Cornish engineers.[2]

A working model steam carriage is on display at the Science Museum (see photos). The standard of workmanship is high, and would not be inconsistent with William West being its maker (West went on to become a clockmaker of high repute). Reference to the photographs indicates how the operating cycle is controlled: a quarter-turn four-way cock is alternately turned through 90 degrees to allow admission admission and exhaust to and from the cylinder. The valve handle is moved by the slotted vertical rod connected to the engine crosshead. Dickenson and Titley dated this to 1798, and stated that its history can be traced back to 1810 when it was at the Soho Foundry in Ancoats, Manchester, of David Whitehead and Co. Their information presumably came from Francis Trevithick's Life of Richard Trevithick[3], which in turn references a 'Letter from Mr. Joseph Radford, in 1850 states that it had been in his family since 1810.' Joseph Radford was probably Joseph Radford, a Manchester ironfounder. The relevant text is: 'A model of Trevithick's, now in the Kensington Museum, spoken of by Mr. Radford as having come from the engine-works of Messrs. Whitehead and Co., Soho Iron Works, Manchester, is probably one of those spoken of by Mrs. Trevithick as having been made prior to 1800. It is a perfect specimen of a high-pressure steam-engine, with cylindrical boiler, adapted to locomotive purposes. It served as a guide to Messrs. Whitehead and Co., who manufactured engines for Trevithick in 1804.' The former Whitehead & Co's Soho Foundry's stock was advertised for sale in 1808, and the foundry itself in 1810.

1800 'In 1800 a high-pressure portable steam-engine was carried in a cart to Wheal Hope, and one was sent to London in charge of Arthur Woolf, the well-known engineer. In the same year the first high-pressure steam-whim was made for Mr. Millett, at a comparatively small cost. This latter application of steam, to supersede the horse-whim in raising mineral from the shafts, was of great importance to the miner. An old account-book, in Cook's Kitchen Mine, has entries bearing Trevithick's doings at that period.' It is interesting to note that the Cook's Kitchen Mine engine worked expansively.[4]

1801 Trevithick built the Puffing Devil and drove it on the roads of Camborne on Christmas Eve. The Puffing Devil was unable to maintain sufficient steam pressure for long periods.

1802 March 26th. 1802 Patent. Trevithick took out a patent for his portable high pressure steam engine with Andrew Vivian. William West becomes a partner in the patent.

1802 Anxious to prove his ideas, he built a stationary engine at the Coalbrookdale Co works in Shropshire, forcing water to a measured height to measure the work done. The engine ran at forty piston strokes a minute, with an unprecedented boiler pressure of 145 psi.

1802 The Coalbrookdale Co were building a railway locomotive in consultation with Trevithick. It is known for certain that the engine was completed. To date the only known information about it comes from a drawing preserved at the London Science Museum and a letter written by Trevithick to his friend, Davies Giddy. The drawing, by John Llewellyn of Merthyr Tydfil, dated December 1803, came to light in 1855. It was donated to the forerunner of the Science Museum in 1862. It was assumed to refer to the Penydarren locomotive, but in 1952 E. A. Forward noted that the drawing was of a 3 ft gauge locomotive, 3ft being the gauge used at Coalbrookdale, whereas the Merthyr tramroad was 4 ft 2 inch gauge.[5]

In 1802 Trevithick built one of his high pressure steam engines to drive an automatic hammer at the Penydarren Ironworks near Merthyr in South Wales. With the assistance of Rees Jones, an employee of the iron works and under the supervision of Samuel Homfray, the proprietor, he mounted the engine on wheels and turned it into a locomotive.

1803 He built the London Steam Carriage and demonstrated it in London.

1803 May 2nd. Trevithick sold a tenth of the patents for his locomotives to Samuel Homfray.

1803 September 8th. One of Trevithick's stationary pumping engines in use at Greenwich exploded, killing 4 men. See Greenwich Explosion.

1803: Arthur Titley determined that up to the end of 1803 Trevithick had erected or upgraded 12, possibly 14 winding engines in Cornwall.[6]

1803/4 Description of one of his earliest High Pressure Engines in The Engineer of 21st May 1920.

1803 Simon Goodrich records an account, probably directly from Trevithick, of the engine at 'Colebrookdale' (Coalbrookdale). Read it in The Engineer 1921/08/26.

1804 The Engineer included photographs of a sample of 1804 rail from the Merthyr Tydfil Railway.

1804 February 21st. Merthyr Tramroad Trial.

1805 Hearing of the success in Wales, Christopher Blackett, proprietor of the Wylam Colliery near Newcastle wrote to Trevithick asking for locomotive designs. These were sent to John Whinfield at Gateshead, Trevithick's agent, who built what was to be Trevithick's second locomotive.

1805 Drives a canal barge by a steam engine and paddle-wheels

1806 Builds the first of three steam dredgers and works them on the Thames

1807 August. Starts working for the Thames Archway Co to build the Thames Drift Tunnel.

1808 Builds the ' Catch me who can' locomotive and demonstrates it in London.

Trevithick went on to research other projects to exploit his high pressure steam engines: boring brass for cannon manufacture, stone crushing, rolling mills, forge hammers, blast furnace blowers as well as the traditional mining applications. He also built a barge powered by paddle wheels and several dredgers.

In 1808 Trevithick entered a partnership with Robert Dickinson, a West India merchant. Dickinson supported several of Trevithick's patents. The first of these was the ' Nautical Labourer'; a steam tug with a floating crane propelled by paddle wheels. However it did not meet the fire regulations for the docks and the Society of Coal Whippers, worried about losing their livelihood, even threatened the life of Trevithick.

1808 July 8th. Issues a challenge that his steam engine can beat any horse in a contest to be held at Newmarket in October. The engine can be seen in the fields adjoining Bedford Nursery near Tottenham Court Road.

In 1809 Trevithick worked on various ideas on improvements for ships: iron floating docks, iron ships, telescopic iron masts, improved ship structures, iron buoys and using heat from the ships boilers for cooking.

1810 Another patent was for the installation of iron tanks in ships for storage of cargo and water instead of in wooden casks. A small works was set up at Limehouse to manufacture them, employing 3 men. The tanks were also used to raise sunken wrecks by placing them under the wreck and creating buoyancy by pumping them full of air.

In 1810 a wreck near Margate was raised in this way but there was a dispute over payment and Trevithick was driven to cut the lashings loose and let it sink again.

1810 May. He caught typhoid and nearly died. By September he had recovered sufficiently to travel back to Cornwall by the ship the 'Falmouth Packet'.

1811 February 5th. He and Dickinson were declared bankrupt. They were not discharged until 1814, Trevithick having paid off most of the partnership debts from his own funds.

1811 He sells his tank patent to Henry Maudslay

In 1811 Francisco Uville was faced with problems draining water from the silver mines of Cerro de Pasco in Peru at high altitude. Boulton and Watt advised that their low-pressure condensing engines would be useless at this altitude, and their components would be too large to transport along mule tracks. Uville was sent to England to investigate using Trevithick's high-pressure steam engine. He bought one and transported it to Peru, and found it to work quite satisfactorily.

c.1812 Trevithick designed what came to be known as Cornish boilers. These were high pressure wrought iron cylindrical boilers with a central fire tube. The exhaust gases were then passed under the boiler, and then along each side, the passages being formed by brickwork. The first such boilers were installed at Dolcoath Mine to supply high pressure steam to three old whim engines, in order to improve efficiency.[7]. The employees rebelled at the changes, and Trevithick he dismissed them and put Jacob Thomas in charge. More power was obtained, and less coal was consumed.

1812 He installed a new 'high pressure' experimental condensing steam engine for pumping at Wheal Prosper. He used a second-hand 24" cylinder and supplied by a ~40 psi boiler. The type became known as the 'Cornish engine' and was the most efficient in the World at that time. Other Cornish engineers contributed to its development but Trevithick's work was key. The performance at Wheal Prosper soon deteriorated, evidently due to deterioration of the boilers.[8]. An important feature of the new Wheal Prosper engine was that the steam was worked expansively.[9] Expansive working had been tried before, but was of little benefit with the low steam pressures then in use.

1812 Installed another high pressure engine, though non-condensing, in a threshing machine on a farm at Probus, Cornwall for Sir Christopher Hawkins. It was very successful and proved to be cheaper to run than the horses it replaced. It ran for 70 years and was then exhibited at the London Science Museum.

1812 Produced the first practical plunger-pole pump and installed it at Wheal Prosper

In one of Trevithick’s more unusual projects, he attempted to build a 'recoil engine' based on the famous model built by Hero of Alexandria in about AD10. This comprised a boiler feeding a hollow axle to route the steam to a Catherine wheel with 2 fine bore steam jets on its circumference, the first 15 feet in diameter and a later model 24 feet in diameter. To get any usable torque, steam had to issue from the nozzles at very high velocity and in large volumes and it proved not to operate with adequate efficiency.

1812 Built a screw propeller for marine propulsion and applied for a patent. He ordered the castings for engine and propellor from Hazledine and Rastrick to be assembled by a London millwright who was building the hull but it was not complete when Richard left for Peru and the millwright never completed the task.

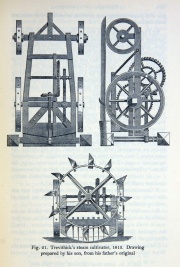

1813 He built an engine for ploughing

In 1813 Uville sailed again for England, landing at Falmouth, close to Trevithick's home, and Uville was able to meet him and discuss the project.

1814 September 1st. Nine engines shipped to Peru

1815 March. R. Trevithick and R. Dickinson of Fore Street, Limehouse, dealer in iron tanks, declared dividend (part of bankruptcy discharge?) [10]

1815 June 6th. Patent 3922 Engine.

Another of his projects was the plunger pole pump, a type of pump used with a beam engine and used widely in Cornwall's tin mines, in which he reversed the plunger to change it into a water-power engine.

1816 June 28th. Trevithick wrote that he had eleven engines of the plunger pole type working. ft for Peru he sold half his rights in the plunger-pole engine to William Sims for £200.

1816 October 20th. Trevithick left Penzance for South America and was away for eleven years. Details at Richard Trevithick: South America

1827 October 9th. Trevithick arrived at Falmouth with few possessions other than the clothes he was wearing. Taking encouragement from earlier inventors who had achieved some successes with similar endeavours, Trevithick petitioned Parliament for a financial grant but he was unsuccessful.

1827 Designed a recoil gun carriage

1828 Visited Holland regarding drainage schemes

1828 October. 'Just after the invention of the steam-carriage which has been in use for the last 20 years on our railways, Mr. Trevithick publicly exhibited it on a circular rail-road constructed on purpose in the Bedford nursery grounds, now Euston square. He also, on the 3rd August in the same year, ran it, and won a large bet, against a race horse' [11]. The engine was called 'Catch Me Who Can'.

1829 Built a closed cycle steam engine followed by a vertical tubular boiler.

In 1830 he invented an early form of storage room heater. It comprised a small fire tube boiler with a detachable flue which could be heated either outside or indoors with the flue connected to a chimney. Once hot the hot water container could be wheeled to where heat was required and the issuing heat could be altered using adjustable doors.

1830 Richard Trevithick of Hayle, Cornwall, Civil Engineer, became a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers.[12]

1832 To commemorate the passing of the Reform Bill he designed a massive column to be 1,000 feet high, being 100 feet in diameter at the base tapering to 12 feet at the top where a statue of a horse would have been mounted. It was to be made of 1,500 10-foot square pieces of cast iron and would have weighed 6,000 tons. There was substantial public interest in the proposal, but it was never built.

About the same time he was invited to do some development work on an engine of a new vessel at Dartford by John Hall (of Dartford), the founder of J. and E. Hall. The work involved a reaction turbine for which Trevithick earned £1,200. He lodged at the Bull Inn, Dartford.

The last invention of Trevithick for which he took a patent on the 19th March, 1833, was for improvements in the steam-engine, and in their application to navigation and locomotion.

1833 After he had been working in Dartford about a year, he was taken ill with pneumonia and had to retire to bed at The Bull. After a week's confinement to bed he died on the morning of 22 April 1833. He was penniless and no relatives or friends had attended his bedside during his illness. His co-workers at Hall's works made a collection for his funeral expenses and acted as bearers and he was buried in an unmarked grave. They also paid a night watchman to guard his grave at night to deter grave robbers as body snatching was common at that time.

A statue depicting Richard Trevithick holding one of his small scale models, stands beside the public library at Camborne. It was erected on the route taken by Puffing Devil in 1801.

One of his four sons, Francis Trevithick, became Locomotive Superintendent of the Northern division of the London and North Western Railway. Francis wrote a detailed account of his father's life and work.

Surviving Engines

See section Trevithick: Surviving Engines.

At least three Trevitihick-designed stationary engines, and one model, were donated to the London Science Museum, but only the model and one full sized engine is displayed.

The remains of a cylinder, cover, piston, rod and crosshead are on display at the Museum of Iron, one of the Ironbridge Gorge Museums.

An 1819 high pressure water engine, recovered from a Derbyshire mine, is on display at the Peak District Mining Museum in Matlock Bath.

Contemporary Accounts - 1804

From the Gloucester Journal, 27th February 1804:-

'New-invented Steam Engine.—On Tuesday se’nnight one of Mr. Trevethick’s Steam-engines was set to work on the colliery of Alexander Raby, Esq. at Llanelly, Carmarthenshire. The base on which it stands does not exceed 14 feet by 12; the boiler is about 5 feet long by 4 in diameter, having its fire-place within, about two thirds from the top, which terminates with a chimney made of plate-iron, so that no masonry or brickwork appears necessary; on the top the boiler, a cylinder of 3 feet in length and 7 inches in diameter is fixed in a horizontal position, containing a piston and rod, which is alternately acted upon by the pressure of the steam from the boiler; which latter is instantly discharged on performing its operation, which it does with velocity of from 15 to 20 strokes in a minute, and may be reduced w.th ease to the slowest possible motion: the piston rod is connected with a crank, and its rotary motion maintained by the action of a fly wheel. The power of this engine is computed to that of four horses, but by an increase of steam might be made equal that of six: the piston is calculated to receive a pressure of 25lbs. to the square inch, which may be increased to 50lbs.- a power, however, not altogether advisable. The expence of fire to generate the ordinary pressure of steam does not exceed one cwt. of coal (to each horse power required) in the 24 hours: its action creates a pleasing astonishment, not being fettered with either condenser or air pump, and one simple cock or valve governing its whole motion; neither is it encumbered with the heavy gearing attached to most other engines. If any drawback appears to operate to the prejudice of this invention, it must arise from the apparatus being so much exposed to the weather, which must during several months in the year, materially operate against the generation of steam, and the perceptual accumulation of dirt on its working parts. But these are inconveniences which will doubtless not escape the attention of the ingenious inventor.

'On Tuesday last, a trial was another of these Engines at Merthyr-Tidvil, Glamorganshire, for the purpose of ascertaining its powers in drawing working carriages of all descriptions, on various kinds of roads; and it was found to perform to admiration all that was expected from it.—In the present instance, the novel application of steam, by means of this truly valuable machine, was made use of to convey along the tram-road 10 tons long weight of bar-iron, from Penydarran iron-works, to the place where it joins the Glamorganshire canal, upwards of 9 miles distance; and it is necessary to observe, that the weight of the load was soon increased from 10 to 15 tons, by about 70 persons riding on the trams, who, drawn thither (as well as many hundreds of others,) by invincible curiosity, were eager to ride, as the expence of this first display of the patentee’s abilities in that country. To those who are not acquainted with the exact principle of this new engine, it may not be improper to observe, that it differs from all others yet brought before the public, by disclaiming the use of condensing water, and discharges its steam into the open air, or applies it the use of heating of fluids, as conveniency may require. The expence of making engines on this principle, does not exceed one half of any the most improved plan, made use of before this appeared; it takes much less coal to work it, and it is only necessary to supply a small quantity of water for the purpose of creating the steam, which is a most essential matter. It performed the journey without feeding the boiler or using any water, and will travel with ease at the rate of five miles an hour.

'The gentleman alluded to in our last Paper, by whose spirited and active patronage the above valuable improvement has attained its present perfection, is Samuel Homfray, Esq. of Penydarran, near Merthyr-Tidvil.'

From the Royal Cornwall Gazette - Saturday 3 March 1804:-

'STEAM ENGINE CART: The long-talked-of plan of applying the power of steam to wheel carriages, appears to have at length succeeded to the wishes of the ingenious Mr. Trevithick, the projector, and the lovers of the arts in general. A trial was made, last week, in Wales, of a Steam Cart, contracted for by a Mr. Humphrey. Four other carts, which it was to take in lead, with that in which the power of steam was applied, were calculated to take seven tons; and a bet of five hundred pounds being dependant on it, a considerable concourse of people attended see it tried; when it moved with ten tons, and seventy men riding on the different carts ; and proceeded at nine miles on a rail road, to the place of its destination. It performed its journey in two hours ; and had it not been for the many obstructions it met with in its way, from large stones and trees lying across the road, from the late storm, it would have performed its journey much sooner. The spectators were much satisfied with its performance, and convinced that it was quite adequate to answer the purpose for which it was designed. Indeed it much exceeded the expectations of the patentee; in consequence of which he received many orders; and the gentleman who betted against it, cheerfully paid his money.

'It is somewhat premature to form any conjectures to which so useful a machine may be applied; as it was discovered in the progress its journey, that it could maintain its course when off the rail road, as it was many times thrown out of its tract, which it easily resumed, and experienced no delay from travelling a considerable space before it could regain its former station. In its route it ascended and descended many ascents and declivities; some which exceeded an inch and half in a yard.

'We are happy to be enabled to give a correct account of our countryman's success in this new and wonderful discovery, especially as we understand it has met with much opposition from many rival mechanics.

1812 Letter Published in The Engineer

The following letter and details were published in The Engineer in 1879 in an article about steam engines at the Kilburn Royal Agricultural Show.

'Nearly all Trevithick's papers from 1803 to 1812 have been destroyed or lost but about 1812 he began to use two old mine account books as letter books, into which he copied rough draughts of his correspondence. The following letter was found in one of these books:- Hayle Foundry, February 13th, 1812.

To Sir Christopher Hawkins, Baronet.

Sir,-I now send you, agreeable to your request, a plan and description of my patent steam engine which I lately erected on your fann for working a thrashing mill. The steam engine is equal in power to four horses, having a cylinder 9in. in diameter. The cylinder with a moderate heat in the boiler makes 30 strokes in a minute! and as many revolutions of the fly-wheel, to every one of which the drum of the thrashing mill, which is 3ft. in diameter, is turned twelve times. The boiler evaporates nine gallons of water in an hour, and works six hours without being replenished. The engine requires only little attention- a common labouring man easily regulates it. The expense of your engine of 4·horse power compared with the expense of four horses is as follows :- £ s d

Original cost of steam engine . . . . . . . . . 80 0 0

Building material and rope. .. . . . .. . 10 0 0

£90 0

Interest on the above, at 5 per cent. 4 10

Wear and tear, at 5 per cent. ... . .. 4 10

Original cost of horse machinery for four horses 60 0 0

Interest on the above, at 5 per cent. ... . .. 3 0 0

wear and tear, at 15 per cent. . . . . . . .. . ..9 0 0

£12 0 0

Two bushels or 164 lb., of coal will do tho work of four horses, costing 2s. oo. Four horses, :~.t 5s. ea.ch, gives 20s. Cost of coal 2s. 6d., as compared with 20s. for horses.

I remain, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

Richard Trevithick.

Accompanying this letter appears a copy of a report

prepared by four individuals, called in as experts to

report on the performance of the machine. The report

runs as follows:-

Cornwall, Feb. 20th, 1812.

Having been requested to witness and report on the effect of steam applied to work a mill for thrashing com at Trewithen, we hereby certify that a fire was lighted under the boiler of the engine five minutes after eight o'clock, and at twenty-five minutes after nine the thrashing mill began to work, in which time one bushel of coal was consumed. That from the time the mill began to work to two minutes after two o'clock, being four hours and three-quarters, 1500 sheaves of barley were thrashed clean, and one bushel of coal more was consumed. We think there was sufficient steam remaining in the boiler to have thrashed from 50 to 100 sheaves more barley, and the water was by no means exhausted. We had the satisfaction to observe that a common labourer regulated the thrashing mill, and in a moment of time made it go faster, slower, or entirely to cease working; we approve of the steadiness and the velocity with which the machine worked, and in every respect we prefer the power of steam ns here applied to that of horses.

(Signed) MATHTEW ROBERTS, Lamellyn.

THOMAS NANKIVILLE, Golden.

MATHEW DOBLE, Bartlever.

Further Reading

An Unpublished Book on The Steam Engine: Trevithick (1826) by John Farey See The Engineer 1920/05/21, p 519

The Mystery of Trevithick's London Locomotives by Loughnan Pendred See The Engineer 1921/03/04, pp 242 - 245

Notes

See Also

Sources of Information

- ↑ [1] Wikipedia entry for Oliver Evans, accessed 9 March 2018

- ↑ [2] Life of Richard Trevithick by F. Trevithick: Volume 1: Chapter 7

- ↑ [3] 'Life of Richard Trevithick' by F. Trevithick: Volume 1: Chapter 7

- ↑ [4] Life of Richard Trevithick by F. Trevithick: Volume 1: Chapter 6

- ↑ 'Loco Motion' by Michael R. Bailey, The History Press, 2014

- ↑ 'Richard Trevithick and the Winding Engine', Arthur Titley, Transactions of the Newcomen Society, 1929, 10:1, 55-68,

- ↑ 'The Harveys of Hayle' by Edmund Vale, 1966/2009

- ↑ 'The Cornish Beam Engine' by D. B. Barton, 1966. p.33

- ↑ 'Richard Trevithick - Giant of Steam' by Anthony Burton, Aurum Press, 2000, p.146

- ↑ The Times, Monday, Mar 27, 1815

- ↑ The Times, Friday, Oct 16, 1829

- ↑ 1830 Institution of Civil Engineers

- The Engineer of 21st May 1920 p519

- The Engineer of 4th June 1920 p573

- [5] Wikipedia

- [6] Trevithick-Day Web Site

- Life of Richard Trevithick by F. Trevithick

- Lives of George and Robert Stephenson by Samuel Smiles: Part 1: Chapter 3

- Time Line - People 1

- Engineers and Mechanics Encyclopedia 1839: Railways: Richard Trevithick

- Richard Trevithick – The Engineer and the Man by H. W. Dickinson and Arthur Titley. Published 1934.

Other Sources

- J. Hodge, Richard Trevithick: an illustrated life of Richard Trevithick, 1771–1833 (1973); repr. (1995) ·

- L. T. C. Rolt, The Cornish giant: the story of Richard Trevithick, father of the steam locomotive (1960)

- W. J. Rowe, Cornwall in the age of the industrial revolution, 2nd edn (1993)

- A. C. Todd, Beyond the blaze: a biography of Davies Gilbert (1967)

- E. Vale, The Harveys of Hayle: engine builders, shipwrights and merchants of Cornwall (1966)

- P. J. Payton, The making of modern Cornwall (1992)

- D. B. Barton, The Cornish beam engine: a survey of its history and development in the mines of Cornwall and Devon from before 1800 to the present day (1969); repr. (1989)

- E. K. Harper, A Cornish giant, Richard Trevithick (1913)

- J. F. Odgers, Richard Trevithick, ‘the Cornish giant’, 1771–1833 (1956)

- G. N. von Tunzelmann, Steam power and British industrialization to 1860 (1978)

- A. L. Rowse, A Cornish anthology, 2nd edn (1982)

- Science Museum, letter and account books

- Science Museum, corresp. and papers relating to Thames Driftway, Hayle Foundry

- Bodleian Library, Oxford, correspondence with William Smith

- Royal Cornwall Museum, corresp. with Davies Gilbert