Difference between revisions of "John Rennie (1761-1821)"

| (19 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:JohnRennie.jpg|thumb| John Rennie (1761-1821). ]] | |||

[[image:Im1961EnV211-p911a.jpg |thumb| John Rennie (1761-1821). ]] | |||

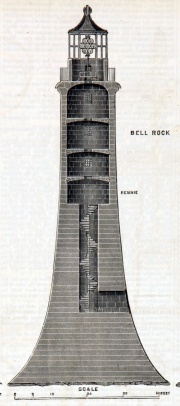

[[Image:Im1879v47Er-Renn.jpg|thumb| 1810. [[Bell Rock Lighthouse]].]] | [[Image:Im1879v47Er-Renn.jpg|thumb| 1810. [[Bell Rock Lighthouse]].]] | ||

| Line 5: | Line 7: | ||

1761 June 7th. Born at Phantassie, near East Linton, East Lothian, the youngest of the nine children of James Rennie (d. 1766), a farmer and owner of a brewery, and his wife, Jean, née Rennie (1720–1783). | 1761 June 7th. Born at Phantassie, near East Linton, East Lothian, the youngest of the nine children of James Rennie (d. 1766), a farmer and owner of a brewery, and his wife, Jean, née Rennie (1720–1783). | ||

1775-77 Attended Dunbar high school | |||

A tinkerer and model builder even as a child, he first worked as a millwright with noted mechanical engineer [[Andrew Meikle]] (inventor of the threshing machine) | A tinkerer and model builder even as a child, he first worked as a millwright with noted mechanical engineer [[Andrew Meikle]] (inventor of the threshing machine). | ||

1780-83 Attended the University of Edinburgh and began work as an engineer, employed by [[Boulton and Watt]] for five years at mill building, and working under [[James Watt]] from 1783. | |||

He was a pioneer in substituting cast iron for wood in structures, at Boulton and Watts' [[Albion Mills, Blackfriars|Albion Mills]] in London, 1789, but this was burnt down by arson in 1791. | |||

1790 Married at Southwark to Martha Ann Mackintosh (1771-1806). | |||

1791 Moved to London and set up his own engineering business, having by then begun to expand into civil engineering. His early projects included | |||

* The [[Lancaster Canal]] (started 1792) | |||

* The [[Chelmer and Blackwater Navigation]] (1793) | |||

* The [[Crinan Canal]] (1794) | |||

* The [[Kennet and Avon Canal]] (also started 1794) | |||

* along with a drainage scheme for draining the Norfolk Fens (1802-1810). | |||

His greatest achievement is said to have been [[Plymouth Breakwater]]; other harbours that he built included those at Berwick, Holyhead, Howth, Kingstown, Newhaven, Queensferry, Ramsgate. He also did work at Chatham, Devonport, Portsmouth and Sheerness dockyards; the [[London Dock Co|London Docks]], and the [[East India Dock Co|East]] and [[West India Dock Co|West India Docks]], and docks at Dublin, Greenock, Hull, Leith and Liverpool; and the Aberdeen and Inverurie canal, as well as the Great Western Canal in Somerset, the Lancashire Canal, including an aqueduct over the Lune, the Polbrook Canal in Cornwall, the Portsmouth and the Rochdale canals. | |||

He also revised the plans for the Royal Canal of Ireland, and various bridges: Southwark, London | |||

and Waterloo, and at Boston, Kelso, Leeds, Musselburgh, New Galloway and Newton Stewart. | |||

He was also successful where others had failed in draining vast tracts of fenland in Lincolnshire | |||

and Cambridge. | |||

1791 Birth of son [[George Rennie]] | |||

1794 Birth of son [[John Rennie]] | |||

Over the next few years he became a famous bridge-builder, combining stone with new cast-iron techniques to create previously unheard-of low, wide elliptical arches, at [[Leeds Bridge]], and in London at [[Waterloo Bridge, London|Waterloo Bridge]] (1811-1817), with its nine equal arches and perfectly flat roadway (thought to be influenced by Thomas Harrison's design of [[Skerton Bridge, Lancaster| Skerton Bridge]] over the River Lune in Lancaster), and [[Southwark Bridge]] (1815-1819). | Over the next few years he became a famous bridge-builder, combining stone with new cast-iron techniques to create previously unheard-of low, wide elliptical arches, at [[Leeds Bridge]], and in London at [[Waterloo Bridge, London|Waterloo Bridge]] (1811-1817), with its nine equal arches and perfectly flat roadway (thought to be influenced by Thomas Harrison's design of [[Skerton Bridge, Lancaster| Skerton Bridge]] over the River Lune in Lancaster), and [[Southwark Bridge]] (1815-1819). | ||

Rennie was also responsible for designing and building docks at Hull, Liverpool, Greenock and Leith and improving the harbours and dockyards at Portsmouth, Chatham and Devonport. Rennie's last project was London Bridge, still under construction when he died in 1821 but completed by his son, | Rennie was also responsible for designing and building docks at Hull, Liverpool, Greenock and Leith and improving the harbours and dockyards at Portsmouth, Chatham and Devonport. Rennie's last project was London Bridge, still under construction when he died in 1821 but completed by his son, [[John Rennie]]. | ||

1819 Rennie introduced the paddle steamboat into the navy | |||

1821 October 4th. Died.<ref>Caledonian Mercury - Thursday 11 October 1821</ref> | 1821 October 4th. Died.<ref>Caledonian Mercury - Thursday 11 October 1821</ref> | ||

1821 October 16th. He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral. Full details. Mourners include his four sons and many other known names.<ref>Morning Chronicle - Wednesday 17 October 1821</ref> | 1821 October 16th. He was buried in [[St Paul's Cathedral]]. Full details. Mourners include his four sons and many other known names.<ref>Morning Chronicle - Wednesday 17 October 1821</ref> | ||

'''250th Anniversary Exhibition''' | |||

In 2011 the Institution of Civil Engineers held an exhibition to commemorate the 250th anniversary of John Rennie's birth. This was supported by an excellent 64-page catalogue illustrating his life and works<ref>[http://www.somersetrivers.org/PDF/John-Rennie-exhibition.pdf] John Rennie 250 - ICE exhibition catalogue</ref> | |||

---- | ---- | ||

''' | '''DNB 1885-1900 Vol 48. | ||

RENNIE, JOHN (1761–1821), civil engineer, youngest son of James Rennie, farmer, was born at Phantassie, Haddingtonshire, on 7 June 1761. George Rennie (1749–1828) [q. v.] was an elder brother. | |||

John showed a taste for mechanics at a very early age, and was allowed to spend much time in the workshop of Andrew Meikle, millwright, the inventor of the threshing machine, who lived at Houston Mill on the Phantassie estate. | |||

After receiving a rudimentary education at the parish school of Prestonkirk, he was sent to the burgh school at Dunbar, and in November 1780 he matriculated at Edinburgh University, where he remained until 1783. He seems to have employed his vacations in working as a millwright, and so to have established a business on his own account. At this early date the originality of his mind was exhibited by the introduction of cast-iron pinions instead of wooden trundles. | |||

In 1784 he took a journey south for the purpose of enlarging his knowledge, visiting James Watt at Soho, Staffordshire. Watt offered him an engagement, which he accepted, and after a short stay at Soho he left for London in 1784 to take charge of the works at the Albion Flour Mills, Blackfriars, for which Boulton & Watt were building a steam-engine. The machinery was all designed by Rennie, and was the most perfect of its kind, a distinguishing feature being the use of iron instead of wood for the shafting and framing. | |||

About 1791 he started in business as a mechanical engineer on his own account in Holland Street, Blackfriars, whence he and his successors long conducted engineering operations of vast importance. | |||

On settling in London Rennie began to pay attention to the construction of canals. He carried out the works in connection with the [[Kennet and Avon Canal]], which was his first civil-engineering undertaking in England. This was followed by the [[Rochdale Canal]], which passes through a difficult country between Rochdale and Todmorden. He subsequently constructed the [[Lancaster Canal]], and in 1802 he revised the plans for the [[Royal Canal of Ireland]] from Dublin to the Shannon near Longford. | |||

For many years he was engaged in extensive drainage operations in the Lincolnshire fens, and in the improvement of the River Witham. The Eau Brink Cut - a new channel for the river Ouse - was on the point of completion at the time of his death. | |||

Among the docks and harbours constructed or improved by Rennie may be mentioned the London docks, East and West India docks, Holyhead harbour, Hull docks, Ramsgate harbour, and the dockyards at Sheerness and Chatham. He devoted much time to the preparation of plans for a government dockyard at Northfleet, but they were not carried out. | |||

Rennie also attained a deserved reputation as a builder of bridges. In the earlier part of his career he built bridges at Kelso and at Musselburgh, the latter presenting a remarkable innovation in the flatness of the roadway. Most of the bridges of any length previously constructed had a considerable rise in the centre. His later efforts show that he was a skilful architect, with a keen sense of beauty of design. Waterloo Bridge, a copy of Kelso Bridge (1810–17), London Bridge, built from his design, though not completed until 1831 after his death, and Southwark Bridge (1815–19) best attest his skill. | |||

The Bell Rock lighthouse, near the entrance to the Friths of Forth and Tay, was built during 1807 and 1810. Rennie is usually credited with the design and execution, but there seems little doubt that he was only nominally responsible for the great undertaking. Robert Stevenson, surveyor to the commissioners of northern lights, drew the original plans, and at his suggestion the commissioners called Rennie into counsel when the works were begun, bestowing on him the honorary title of chief engineer. Stevenson did not accept the modifications proposed by Rennie, but the two men remained on friendly terms. Rennie visited the lighthouse while it was building. According to Robert Louis Stevenson, Stevenson's grandson, the board of northern lights paid Stevenson alone when the lighthouse was completed. When Stevenson died in 1850 the board put on record in its minutes that to him was ‘due the honour of conceiving and executing the Bell Rock lighthouse.’ But Rennie and his friends always claimed that the general advice which Rennie gave Stevenson entitled him to rank the building among his own achievements (see art. Stevenson, Robert ‘A Family of Engineers’ in R. L. Stevenson's Works, Edinburgh, ed. 1896, xviii. 273–4; paper by David Stevenson in Civil Engineers' and Architects' Journal, 1862). | |||

Of all Rennie's works, that which appeals most strongly to the imagination is perhaps the breakwater at Plymouth, consisting of a wall a mile in length across the Sound, in deep water, and containing 3,670,444 tons of rough stone, besides 22,149 cubic yards of masonry on the surface. This colossal work was first proposed in a report by Rennie, dated 22 April 1806; an order in council authorising its commencement was issued on 22 June 1811, and the first stone was deposited on 12 Aug. following. The work was completed by his son [see Rennie, Sir John]. | |||

Rennie was a man of unbounded resource and originality. During the improvement of Ramsgate harbour he made use of the diving-bell, which he greatly improved. He is generally credited with the invention of the present form of steam-dredging machine with a chain of buckets, but in this he seems to have been anticipated by Sir Samuel Bentham (cf. Mechanics' Magazine, xliii. 114, li. 126). But he was certainly the first to use it on an extensive scale, which he did during the construction of the Hull docks (1803–9), when he devised a steam dredger to overcome the difficulties of that particular work, and apparently without any knowledge of Bentham's invention. Another expedient was the use of hollow walls, which was suggested by the necessity of providing an extensive bearing surface for the foundations of a wall in loose ground. Walls built upon this plan were largely used by Rennie. | |||

The distinguishing characteristics of Rennie's work were firmness and solidity, and it has stood the test of time. He was most conscientious in the preparation of his reports and estimates, and he never entered upon an undertaking without making himself fully acquainted with the local surroundings. He was devoted to his profession, and, though he was a man of strong frame and capable of great endurance, his incessant labours shortened his life. He was elected F.R.S. on 29 March 1798. | |||

He died, after a short illness, at his house in Stamford Street, London, on 4 Oct. 1821, and was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral. He married early in life Martha, daughter of E. Mackintosh, who predeceased him; by her he left several children, two of whom, George (1791–1866) and Sir John, are separately noticed. | |||

---- | ---- | ||

''' 1821 Obituary.<ref>Caledonian Mercury - Saturday 13 October 1821</ref> | ''' 1821 Obituary.<ref>Caledonian Mercury - Saturday 13 October 1821</ref> | ||

The death of J. Rennie, Esq. | The death of J. Rennie, Esq. is a national calamity. His loss cannot be adequately supplied by any living artist, for, though we have many able engineers, We know of none who so eminently possess solidity of judgment with profound knowledge, and the happy tact of applying to every situation, where he was called upon to exert his faculties, the precise form of remedy that was wanting to the existing evil | ||

Whether it was to stem the torrent and violence of the most boisterous sea - to make new harbours, or to render those safe which were before dangerous or inaccessible - to redeem districts of fruitful land from encroachment by the ocean, or to deliver them from the pestilence of stagnant marsh - to level hills, or to tie them together by aqueducts or arches, or by embankment to raise the valley between them - to make bridges that for beauty surpass all others, and for strength seemed destined to endure to the latest posterity, Mr Rennie had no rival. | Whether it was to stem the torrent and violence of the most boisterous sea - to make new harbours, or to render those safe which were before dangerous or inaccessible - to redeem districts of fruitful land from encroachment by the ocean, or to deliver them from the pestilence of stagnant marsh - to level hills, or to tie them together by aqueducts or arches, or by embankment to raise the valley between them - to make bridges that for beauty surpass all others, and for strength seemed destined to endure to the latest posterity, Mr Rennie had no rival. | ||

| Line 59: | Line 115: | ||

==Sources of Information== | ==Sources of Information== | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Rennie_%28engineer%29] | * [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Rennie_%28engineer%29 Wikipedia] | ||

* [[Leaders of Modern Industry by G. Barnett Smith: The Rennies]] | * [[Leaders of Modern Industry by G. Barnett Smith: The Rennies]] | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rennie (the elder), John}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Rennie (the elder), John}} | ||

[[Category: Biography]] | [[Category: Biography]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category: Biography - Civil]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category: Biography - Canals]] | ||

[[Category: Births 1760-1769]] | [[Category: Births 1760-1769]] | ||

[[Category: Deaths 1820-1829]] | [[Category: Deaths 1820-1829]] | ||

Revision as of 12:53, 6 June 2020

John Rennie (1761-1821)

1761 June 7th. Born at Phantassie, near East Linton, East Lothian, the youngest of the nine children of James Rennie (d. 1766), a farmer and owner of a brewery, and his wife, Jean, née Rennie (1720–1783).

1775-77 Attended Dunbar high school

A tinkerer and model builder even as a child, he first worked as a millwright with noted mechanical engineer Andrew Meikle (inventor of the threshing machine).

1780-83 Attended the University of Edinburgh and began work as an engineer, employed by Boulton and Watt for five years at mill building, and working under James Watt from 1783.

He was a pioneer in substituting cast iron for wood in structures, at Boulton and Watts' Albion Mills in London, 1789, but this was burnt down by arson in 1791.

1790 Married at Southwark to Martha Ann Mackintosh (1771-1806).

1791 Moved to London and set up his own engineering business, having by then begun to expand into civil engineering. His early projects included

- The Lancaster Canal (started 1792)

- The Chelmer and Blackwater Navigation (1793)

- The Crinan Canal (1794)

- The Kennet and Avon Canal (also started 1794)

- along with a drainage scheme for draining the Norfolk Fens (1802-1810).

His greatest achievement is said to have been Plymouth Breakwater; other harbours that he built included those at Berwick, Holyhead, Howth, Kingstown, Newhaven, Queensferry, Ramsgate. He also did work at Chatham, Devonport, Portsmouth and Sheerness dockyards; the London Docks, and the East and West India Docks, and docks at Dublin, Greenock, Hull, Leith and Liverpool; and the Aberdeen and Inverurie canal, as well as the Great Western Canal in Somerset, the Lancashire Canal, including an aqueduct over the Lune, the Polbrook Canal in Cornwall, the Portsmouth and the Rochdale canals.

He also revised the plans for the Royal Canal of Ireland, and various bridges: Southwark, London and Waterloo, and at Boston, Kelso, Leeds, Musselburgh, New Galloway and Newton Stewart.

He was also successful where others had failed in draining vast tracts of fenland in Lincolnshire and Cambridge.

1791 Birth of son George Rennie

1794 Birth of son John Rennie

Over the next few years he became a famous bridge-builder, combining stone with new cast-iron techniques to create previously unheard-of low, wide elliptical arches, at Leeds Bridge, and in London at Waterloo Bridge (1811-1817), with its nine equal arches and perfectly flat roadway (thought to be influenced by Thomas Harrison's design of Skerton Bridge over the River Lune in Lancaster), and Southwark Bridge (1815-1819).

Rennie was also responsible for designing and building docks at Hull, Liverpool, Greenock and Leith and improving the harbours and dockyards at Portsmouth, Chatham and Devonport. Rennie's last project was London Bridge, still under construction when he died in 1821 but completed by his son, John Rennie.

1819 Rennie introduced the paddle steamboat into the navy

1821 October 4th. Died.[1]

1821 October 16th. He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral. Full details. Mourners include his four sons and many other known names.[2]

250th Anniversary Exhibition

In 2011 the Institution of Civil Engineers held an exhibition to commemorate the 250th anniversary of John Rennie's birth. This was supported by an excellent 64-page catalogue illustrating his life and works[3]

DNB 1885-1900 Vol 48.

RENNIE, JOHN (1761–1821), civil engineer, youngest son of James Rennie, farmer, was born at Phantassie, Haddingtonshire, on 7 June 1761. George Rennie (1749–1828) [q. v.] was an elder brother.

John showed a taste for mechanics at a very early age, and was allowed to spend much time in the workshop of Andrew Meikle, millwright, the inventor of the threshing machine, who lived at Houston Mill on the Phantassie estate.

After receiving a rudimentary education at the parish school of Prestonkirk, he was sent to the burgh school at Dunbar, and in November 1780 he matriculated at Edinburgh University, where he remained until 1783. He seems to have employed his vacations in working as a millwright, and so to have established a business on his own account. At this early date the originality of his mind was exhibited by the introduction of cast-iron pinions instead of wooden trundles.

In 1784 he took a journey south for the purpose of enlarging his knowledge, visiting James Watt at Soho, Staffordshire. Watt offered him an engagement, which he accepted, and after a short stay at Soho he left for London in 1784 to take charge of the works at the Albion Flour Mills, Blackfriars, for which Boulton & Watt were building a steam-engine. The machinery was all designed by Rennie, and was the most perfect of its kind, a distinguishing feature being the use of iron instead of wood for the shafting and framing.

About 1791 he started in business as a mechanical engineer on his own account in Holland Street, Blackfriars, whence he and his successors long conducted engineering operations of vast importance.

On settling in London Rennie began to pay attention to the construction of canals. He carried out the works in connection with the Kennet and Avon Canal, which was his first civil-engineering undertaking in England. This was followed by the Rochdale Canal, which passes through a difficult country between Rochdale and Todmorden. He subsequently constructed the Lancaster Canal, and in 1802 he revised the plans for the Royal Canal of Ireland from Dublin to the Shannon near Longford.

For many years he was engaged in extensive drainage operations in the Lincolnshire fens, and in the improvement of the River Witham. The Eau Brink Cut - a new channel for the river Ouse - was on the point of completion at the time of his death.

Among the docks and harbours constructed or improved by Rennie may be mentioned the London docks, East and West India docks, Holyhead harbour, Hull docks, Ramsgate harbour, and the dockyards at Sheerness and Chatham. He devoted much time to the preparation of plans for a government dockyard at Northfleet, but they were not carried out.

Rennie also attained a deserved reputation as a builder of bridges. In the earlier part of his career he built bridges at Kelso and at Musselburgh, the latter presenting a remarkable innovation in the flatness of the roadway. Most of the bridges of any length previously constructed had a considerable rise in the centre. His later efforts show that he was a skilful architect, with a keen sense of beauty of design. Waterloo Bridge, a copy of Kelso Bridge (1810–17), London Bridge, built from his design, though not completed until 1831 after his death, and Southwark Bridge (1815–19) best attest his skill.

The Bell Rock lighthouse, near the entrance to the Friths of Forth and Tay, was built during 1807 and 1810. Rennie is usually credited with the design and execution, but there seems little doubt that he was only nominally responsible for the great undertaking. Robert Stevenson, surveyor to the commissioners of northern lights, drew the original plans, and at his suggestion the commissioners called Rennie into counsel when the works were begun, bestowing on him the honorary title of chief engineer. Stevenson did not accept the modifications proposed by Rennie, but the two men remained on friendly terms. Rennie visited the lighthouse while it was building. According to Robert Louis Stevenson, Stevenson's grandson, the board of northern lights paid Stevenson alone when the lighthouse was completed. When Stevenson died in 1850 the board put on record in its minutes that to him was ‘due the honour of conceiving and executing the Bell Rock lighthouse.’ But Rennie and his friends always claimed that the general advice which Rennie gave Stevenson entitled him to rank the building among his own achievements (see art. Stevenson, Robert ‘A Family of Engineers’ in R. L. Stevenson's Works, Edinburgh, ed. 1896, xviii. 273–4; paper by David Stevenson in Civil Engineers' and Architects' Journal, 1862).

Of all Rennie's works, that which appeals most strongly to the imagination is perhaps the breakwater at Plymouth, consisting of a wall a mile in length across the Sound, in deep water, and containing 3,670,444 tons of rough stone, besides 22,149 cubic yards of masonry on the surface. This colossal work was first proposed in a report by Rennie, dated 22 April 1806; an order in council authorising its commencement was issued on 22 June 1811, and the first stone was deposited on 12 Aug. following. The work was completed by his son [see Rennie, Sir John].

Rennie was a man of unbounded resource and originality. During the improvement of Ramsgate harbour he made use of the diving-bell, which he greatly improved. He is generally credited with the invention of the present form of steam-dredging machine with a chain of buckets, but in this he seems to have been anticipated by Sir Samuel Bentham (cf. Mechanics' Magazine, xliii. 114, li. 126). But he was certainly the first to use it on an extensive scale, which he did during the construction of the Hull docks (1803–9), when he devised a steam dredger to overcome the difficulties of that particular work, and apparently without any knowledge of Bentham's invention. Another expedient was the use of hollow walls, which was suggested by the necessity of providing an extensive bearing surface for the foundations of a wall in loose ground. Walls built upon this plan were largely used by Rennie.

The distinguishing characteristics of Rennie's work were firmness and solidity, and it has stood the test of time. He was most conscientious in the preparation of his reports and estimates, and he never entered upon an undertaking without making himself fully acquainted with the local surroundings. He was devoted to his profession, and, though he was a man of strong frame and capable of great endurance, his incessant labours shortened his life. He was elected F.R.S. on 29 March 1798.

He died, after a short illness, at his house in Stamford Street, London, on 4 Oct. 1821, and was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral. He married early in life Martha, daughter of E. Mackintosh, who predeceased him; by her he left several children, two of whom, George (1791–1866) and Sir John, are separately noticed.

1821 Obituary.[4]

The death of J. Rennie, Esq. is a national calamity. His loss cannot be adequately supplied by any living artist, for, though we have many able engineers, We know of none who so eminently possess solidity of judgment with profound knowledge, and the happy tact of applying to every situation, where he was called upon to exert his faculties, the precise form of remedy that was wanting to the existing evil

Whether it was to stem the torrent and violence of the most boisterous sea - to make new harbours, or to render those safe which were before dangerous or inaccessible - to redeem districts of fruitful land from encroachment by the ocean, or to deliver them from the pestilence of stagnant marsh - to level hills, or to tie them together by aqueducts or arches, or by embankment to raise the valley between them - to make bridges that for beauty surpass all others, and for strength seemed destined to endure to the latest posterity, Mr Rennie had no rival.

Every part of the United Kingdom possesses monuments to his glory, and they are stupendous as they are useful. They will present to our children's children objects of admiration for their grandeur, and of gratitude to the author for their utility.

Compare the works of Mr Rennie with the most boasted exploits of the French engineers, and remark how they tower above them. Look at the breakwater at Plymouth, in comparison with the cassoons at Cherburg - any one of his canals with that of Ourke, and his Waterloo bridge with that of Neuilly. Their superiority is acknowledged by every liberal Frenchmen.

He cultivated his art with the most enthusiastic ardour, and, instead of being merely a theorist, he prepared himself for practical efficiency by visiting, and minutely inspecting every work of magnitude in every country that bear similitude with those which he might he called on to construct, and his library abounds in the richest collection of scientific writings of that of any individual.

The loss of such a man is irreparable. Cut off in the full vigour of his mind, his death seems to suspend for a time the march of national improvement, until the just fame of his merit shall animate our rising artists to imitate his great example, and to prepare themselves by study and observation to overcome, as he did, the most formidable impediments to the Progress of human enterprise, of industry, and of increased facility in all the arts of life.

The integrity of Mr Rennie in the fulfilment of his labours was equal to his genius in the contrivance of his plans and machinery. He would suffer none of the modern subterfuges for real strength to be resorted to by the contractors employed to execute what he had undertaken. Every thing, he did was for futurity, as well, as present advantage.

An engineer is not like an architect. He has no commission on the amount of his expenditure; if he had, Mr Rennie would have been one of the most opulent men in England, for many millions have been expended under his eye. But his glory was in the justice of his proceeding, and his enjoyment in the success of his labours.

It was only as a millwright that he engaged himself to execute the work he planned, and in this department society is indebted to him for economising the power of water, so as to give an increase of energy, by its specific gravity, to the natural fall of streams, and to make his mills equal to fourfold the produce of those which, before his time, depended solely on the impetus of the current. His mills of the greatest size work as smoothly as cloak-work, and, by the alternate contact of wood and iron, are less liable to the hazard of fire by friction. His mills, indeed, are models of perfection.

If the death of such a man is a national loss what must it be to his private friends and to his amiable family? Endeared by all who knew him by the gentleness of his temper, the cheerfulness with which he communicated the riches of his mind, and forwarded the views of those who made useful discoveries or improvements in machinery or implements, procured him universal respect.-

He gave to inventors all the benefits of his experience, removed difficulties which had not occurred to the author, or suggested alterations which adapted the instrument to its use. No jealousy nor self-interest ever prevented the exercise of this free and unbounded communication, for the love of science was superior in his mind to all mercenary feeling.

Mr Rennie was born in Scotland, and from his earliest years devoted himself to the art of a civil engineer. He was the intimate friend and companion of his excellent countryman, the late Mr Watt; their habits and pursuits were similar. They worked together, and to their joint efforts are we chiefly indebted for the gigantic power of the steam-engine in all our manufactories.

He married early in life Miss Mackintosh, a beautiful young woman, whom he had the misfortune to lose some years ago, but who left him an interesting and accomplished family. They have now to lament the loss of the best of parents, who, though possessed of a constitution and frame so robust as to give the promise of a very long life, sunk under an attack at the early age of 64.